An easy riverside walk packed with fascinating stories of colonial Harrington.

As an island nation, Australia’s European history is inextricably linked to our oceans and seas: they carried our explorers, our settlers and soldiers, our produce, our hopes and dreams too. All of it in ships and many of them built right here in Harrington.

If you’re enthralled by the maritime history of the early days of the colony of New South Wales, then this Heritage Riverwalk is very rewarding. You’ll discover fascinating facts, titbits of history and stories of creating new lives in a new world: ship building, ship wrecks, missing ships, even a ship hijacked by honourable Maoris unfairly imprisoned.

Remember that sea travel in those days was slow and treacherous. The now-famous nearby lighthouses of the Barrington Coast were not built until later: Sugarloaf Point at Seal Rocks (1875) and Crowdy Head (1878). And few people could swim in those days, so anyone stepping aboard a ship truly pinned their hopes to the quality of the vessel and the expertise of the crew.

Interpretive signs along this riverwalk celebrate the rich history of Harrington’s ship building and some early pioneers of this stretch of the Manning River.

And if you’re a resident of Harrington Waters, you may find your street named here and why. This is how history sometimes lives: quietly in the background but always part of our daily lives.

(Information and images below are courtesy of Harrington and Surrounds Business and Community Associations Inc.)

The best easy walk at Harrington.

If you like your history in chronological order, start at the main panel at Alexander Newton Reserve off Pretoria Parade and follow the other 8 signs. Otherwise you can walk backwards through time, starting at Gordon Smith Reserve off Beach Street.

The Newtons of Pelican: pioneers, shipbuilders, mariners

Thirty ocean-going ships were built along this riverbank at the Pelican Shipyard between 1846 and 1878. It was said to be once the largest shipyard in the southern hemisphere. The shipyard extended from the jetty and pine tree you can see upriver, to the point visible downriver known as Pelican Point.

From Scotland to the Manning River

Alexander Newton Senior was an adventurer. Born in Scotland in 1810, he was apprenticed as a shipwright. Working as a carpenter and whaler, he sailed the world’s oceans from the Arctic Circle to the Southern Ocean. He disembarked in Sydney in 1835. Later that year he was at Scotchtown (in Kempsey) building sailing ships with partners, including William Malcolm. They built 11 ships before the partnership dissolved.

In 1846 Newton and Malcolm moved to this riverbank where, under a land grants scheme, they owned 200 hectares. Forests of ship-building timbers and a deep river made their land ideal for ship building. They established a shipyard, calling it “Pelican”.

Learning seamanship in the tough whaling school, Newton later became a master mariner. A skilful shipwright, he built alongside his workers. He interspersed shipbuilding with trading voyages in his ships, going to sea about every five years.

The Pelican Shipyard

The Pelican Shipyard was called Baruah until the early 1850s. The schooner Baruah was launched in 1851 at the shipyard and bore the figurehead of a bird. Was it a Pelican? No images exist for this ship.

Ship-building timbers came from the floodplain here and from higher ground nearby: paperbark for the ship knees (curved bracings); ironbark for keels; white beech and cedar for decking, joinery and interior finishing; and blackbutt and spotted gum for planking and frames. Timber for masts and spars came from Mitchells Island – that’s it across the river.

Shipwrights, apprentices, cooks, labourers, blacksmiths and sawyers lived in huts at the Pelican Shipyard, working 12-hour days, six days a week.

In the 31 years to 1878, Newton, Malcolm (until he died in 1856) and Newton’s sons built, launched, sometimes owned and sailed, 30 ocean-going ships. All but the paddle-steamer Huntress were sailing ships.

Carrying cedar, hardwoods, farm produce and passengers from the Manning Valley along the east coast, they returned with provisions for the district. They also traded globally including to booming goldfields.

The Pelican ships were well-built and long-lasting, despite being worked hard and driven relentlessly. “Mr Newton’s reputation ranks second to none in the colonies for the staunchness of the vessels built by him”, The Manning River News reported in 1865.

The Newton Family

Alexander Newton married Hannah Scott in Sydney in 1846. In early 1849, Hannah and their first born, Alexander Newton Junior (Alex), moved from Sydney to join him. Alexander and Hannah raised 11 children at the yard. Ten were born there.

All five sons were apprenticed as Pelican shipwrights; all went to sea in Newton ships and all became ships’ masters. All six daughters had a ship named after them – Jessie (launched in 1856), Ellen (1859), Hannah (1867), Rebecca Jane (1871), Alice Maud (1872), and May Newton (1878).

When his father went to sea in 1867 Alex, aged 20, took charge of the shipyard. On his father’s return Alex sailed to many countries as first mate on the Newton’s Rebecca Jane and, in 1873, he was appointed her master. In 1876, back at Pelican, Alex and his father built the Alexander Newton which Alex sailed as master for the next eight years.

Alex married Annie Howlett in 1884. They had eight children and lived on their “Belmore” property at the mouth of Cattai Creek. Retiring from the sea in 1885 he turned his hand to grazing and dairying, becoming a director of the Manning River Cooperative Dairy Company.

Alexander Newton’s other sons were Charles, William, Robert and Peter. Robert, gaining his Master’s Certificate in 1885, took command of the May Newton. In 1892, with Robert as master, she disappeared without trace, all hands lost.

Alexander and Hannah valued education. Harrington’s first school (Pelican Point) was on his land. Two daughters taught at Harrington’s third school, the Cattai Creek School, built on Alex’s “Belmore” property. Hannah taught there from 1884-1891, Ellen from 1891-1900.

1. Fighting for Survival

The Rosetta Joseph (1847) was the first ship built by Alexander Newton Snr and William Malcolm at their Pelican Shipyard, 700m upriver from here.

The 265-ton barque ran aground at night on Elizabeth Reef, 180km north of Lord Howe Island, on December 1, 1850. All on board, including two women and two children, abandoned ship.

Heading for Australia in two lifeboats they sailed, rowed, and bailed for their lives for eight days. They battled massive storms, lightning, seas and currents. To lighten the boats they jettisoned clothes, blankets, even gold.

Of day two, a survivor wrote: “We laboured and made much water, the sea at this time running mountains high. During this frightful night we expected … to be swamped.” And, on day six, “another frightful night … we all but drowned, from the sea continually washing over.” But they didn’t drown, making landfall at Port Macquarie on 10 December 1850.

The journey, estimated to be at least 1,130 km, is described as one of the great open-boat survival stories in NSW maritime history.

2. From the Manning to the Maori wars

The schooner Rifleman was embroiled in the New Zealand wars of 1845 to 1872, fought between Maori people and British colonialists.

The Rifleman sailed to the Chatham Islands (800km east of the New Zealand South Island) in 1868 carrying cargo for Maoris imprisoned without trial. While docked, Maori warrior Te Kooti hijacked the ship, leading an escape by 298 men, women and children. No blood was shed.

Te Kooti forced the crew to take them to the North Island. In return he promised the safety of their lives and their ship. He kept his word. Over the next four years Te Kooti led a series of bloody skirmishes with colonial authorities.

The Rifleman struck rocks off the North Island in 1871 and was badly damaged. Repaired, she resumed service but, two months later, she and her six crew disappeared without trace.

Rifleman Place in Harrington honours the ship.

3. A tale of two steamers

The Fire King:

The Fire King transported Manning Valley produce (including maize and pigs) and passengers between Tinonee and Sydney on a weekly run. She boasted first-class accommodation. Returning, she carried supplies for farms, businesses and households.

The first consignment for Harrington’s second school was part of the cargo in 1872. It included scripture books, slates, pencils, pens and ink powder.

Boating excursions and picnic days to Harrington were social highlights for the Manning’s upriver residents. On one Fire King trip in 1868 with 300 aboard The Manning River News reported that “dancing was vigorously proceeded with throughout the whole excursion”.

Fire King was wrecked on the north beach at the entrance to the Manning in 1873. All aboard were saved.

Fireking Place is not far from here.

The Diamantina:

The Diamantina competed with the Fire King for freight and passengers on the Manning River and open sea.

In the early 1870s the Manning bar was only crossable at high tide, in daylight. Of one crossing a passenger wrote: “Of all the bad river entrances on the coast the Manning is considered the worst, bad at the best of seasons, with a list of wrecks really formidable … When among the breakers I naturally felt a little nervous, glances were occasionally thrown towards the life buoys which were providentially close to hand; but the danger was soon past.”

But, on 31 March 1881 a crossing failed: she was stranded, wrecked, salvaged and sold. But her name lives on as Diamantina Circuit – the road behind you beyond the fig tree.

4. Early schools and the Newtons

Pelican Point School, Harrington’s first school, was established here. This land was part of the riverbank holding belonging to pioneer and shipbuilder Alexander Newton.

Newton, and Harrington’s second maritime pilot, Captain Joseph Bradley, established the school in 1866 for children of families from the Pelican Shipyard and the pilot service.

Newton provided the land; the community provided the building and furniture. The government paid the teacher and running costs.

The school closed in 1869 when numbers dropped below 25. It reopened for a year from December 1870 as a “half-time school” with the school on Mambo Island, then closed permanently.

Cattai Creek School was established in 1884 by Newton’s daughter Hannah. Alexander Newton donated the land. Hannah taught there until November 1891; her sister Ellen then taught there until 1900.

The Manning River News (1902) said: “A very enjoyable picnic in connection with the Cattai Public School was held at Chinamans Point … on 10th instant, King’s Birthday … the grounds … placed at their disposal by Captain Newton.”

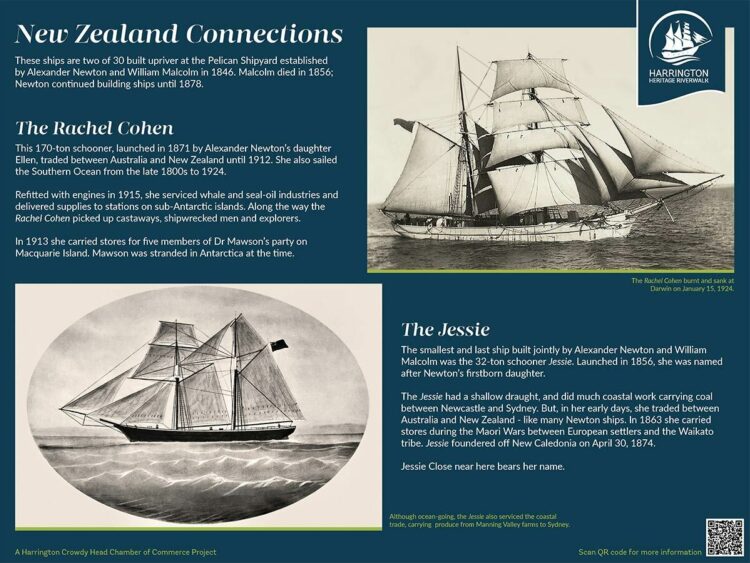

5. New Zealand connections

These ships are two of 30 built upriver at the Pelican Shipyard established by Alexander Newton and William Malcolm in 1846. Malcolm died in 1856; Newton continued building ships until 1878.

The Rachel Cohen:

This 170-ton schooner, launched in 1871 by Alexander Newton’s daughter Ellen, traded between Australia and New Zealand until 1912. She also sailed the Southern Ocean from the late 1800s to 1924.

Refitted with engines in 1915, she serviced whale and seal-oil industries and delivered supplies to stations on sub-Antarctic islands. Along the way the Rachel Cohen picked up castaways, shipwrecked men and explorers.

In 1913 she carried stores for five members of Dr Mawson’s party on Macquarie Island. Mawson was stranded on Antarctica at the time.

The Jessie:

The smallest and last ship built jointly by Alexander Newton and William Malcolm was the 32-ton schooner Jessie. Launched in 1856, she was named after Newton’s firstborn daughter.

The Jessie had a shallow draught and did much coastal work carrying coal between Newcastle and Sydney. But in her early days, she traded between Australia and New Zealand – like many Newton ships. In 1863 she carried stores during the Maori Wars between European settlers and the Waikato tribe. Jessie foundered off New Caledonia on 30 April, 1874.

Jessie Close near here bears her name.

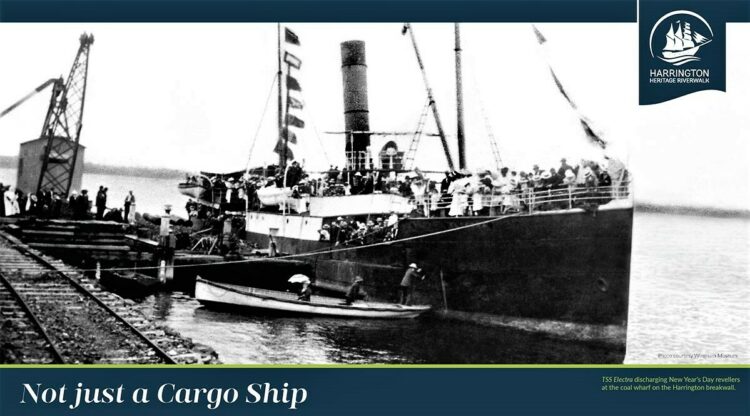

6. Not just a cargo ship

The Electra was probably the most prestigious and popular vessel on the Manning in the late 1890s. She was the first Australian ship fitted with a generator for lighting and refrigeration.

Working the Manning trade to Sydney from 1891, Electra picked up and discharged goods and passengers in Wingham, Taree, Cundletown, Croki and Harrington. On one journey in 1900, her cargo included 1,000 bricks, 10 sewing machines and a horse for Croki. That year, the outlaw Jimmy Governor was a passenger, transported under guard from Wingham to Sydney.

But Electra was also a party ship. Her New Year’s Day excursion to Harrington was the biggest social event of the year, a charity fundraiser. Bunting, fruit and cordial stalls lined the decks and bands played. Starting early from Wingham, she picked up passengers along the way. On New Year’s Day, 1892, she carried hundreds of partygoers, all dressed in their finest.

Electra ran aground on the bar during a picnic to Harrington in April 1907. All 90 passengers were brought ashore by rope, pulley and breeches buoy.

Electra Parade is named for her.

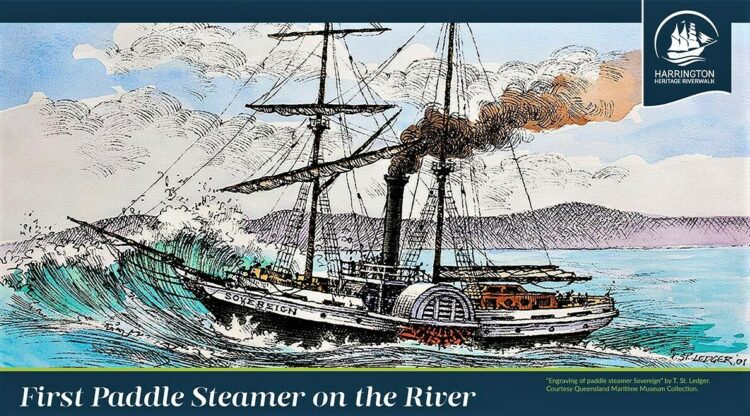

7. First paddle steamer on the Manning

The Sovereign was the largest ship, and first paddle steamer, to enter the Manning River. It crossed the dangerous bar without a pilot in 1842.

The crossing was difficult. Grounding near the river mouth, she took several hours to get free. Travelling upriver to Taree the Sovereign loaded cargo of 94 bales of wool and a quantity of wheat.

The captain noted the river afforded “great facilities for steam navigation”, its banks “composed of an exceeding rich and fertile” soil suitable for agriculture, the surrounding forests abounding “with rosewood, cedar, and hardwood, of a very fine description.”

The schooner-rigged, 119-ton Sovereign was wrecked attempting the South Passage from Moreton Bay in 1847. Forty-four passengers and crew drowned; ten survived, including the captain, saved by six local Aboriginal men. One survivor said “They swum us to land, took us to their camp, tended our wounds, wrapped us in their blankets …” An inquiry found the captain at fault for overloading her.

The houses behind you are on Sovereign Avenue.

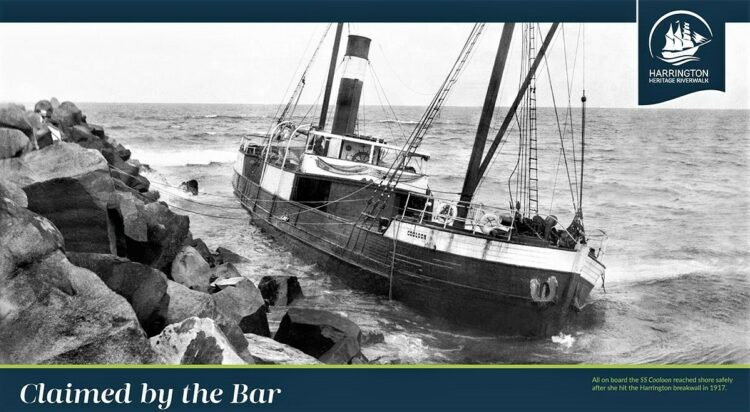

8. Claimed by the bar

Timber was a major export from the Manning Valley by the late 1860s. There were three big timber mills on the nearby Lansdowne River in 1870. Langley Brothers operated one of them. They provided accommodation and a general store for their 50 mill workers.

The Cooloon was part of a small shipping fleet they owned, transporting timber to Sydney. Also carrying general cargo and up to 16 passengers, she worked between Sydney and the Tweed.

Built on the Lansdowne River in 1904 the Cooloon, a wooden 141-ton steamship with crew of 14, was tastefully fitted throughout. Mahogany and pine panelling in the saloon was painted with country scenes by women of the Manning.

The Manning River sandbar claimed Cooloon when she hit the breakwater in 1917 while entering the river in ballast. No lives were lost, and the Marine Court exonerated the captain. Her machinery was recovered and fitted to the Langley Brothers steamship Cobaki.

Cooloon and Duroby (another Langley ship) are Harrington Waters street names.